Heritage artwork at the Globe Works: The Hand Forger

Discover the story behind the artwork

Created by Wessex Archaeology in 2022, these panels were commissioned by the Globe Works to commemorate the outstanding and unique heritage of the building and depict people and scenes from its industrial past.

The forming of steel into a blade has always been called forging in Sheffield; the term ‘smith’ was never used. This work was undertaken by a cutler or specialist forger.

The forging process comprised the heating of metal which was hammered to create the blade. The cutler or forger would use bars of steel or iron with a thin strip of steel forged together to then create the blade with a good steel cutting edge. Because steel was much more expensive than iron, the steel would be welded onto iron to create the cutting edge.

Forging needed to be done quickly whilst the metal was at the correct forging heat. This was done with an aim of keeping reheating to a minimum which would slow down production rates, and an average blade could be forged in less than a minute. Although the forgers would work very quickly, it was difficult for them to kept to this pace day in day out.

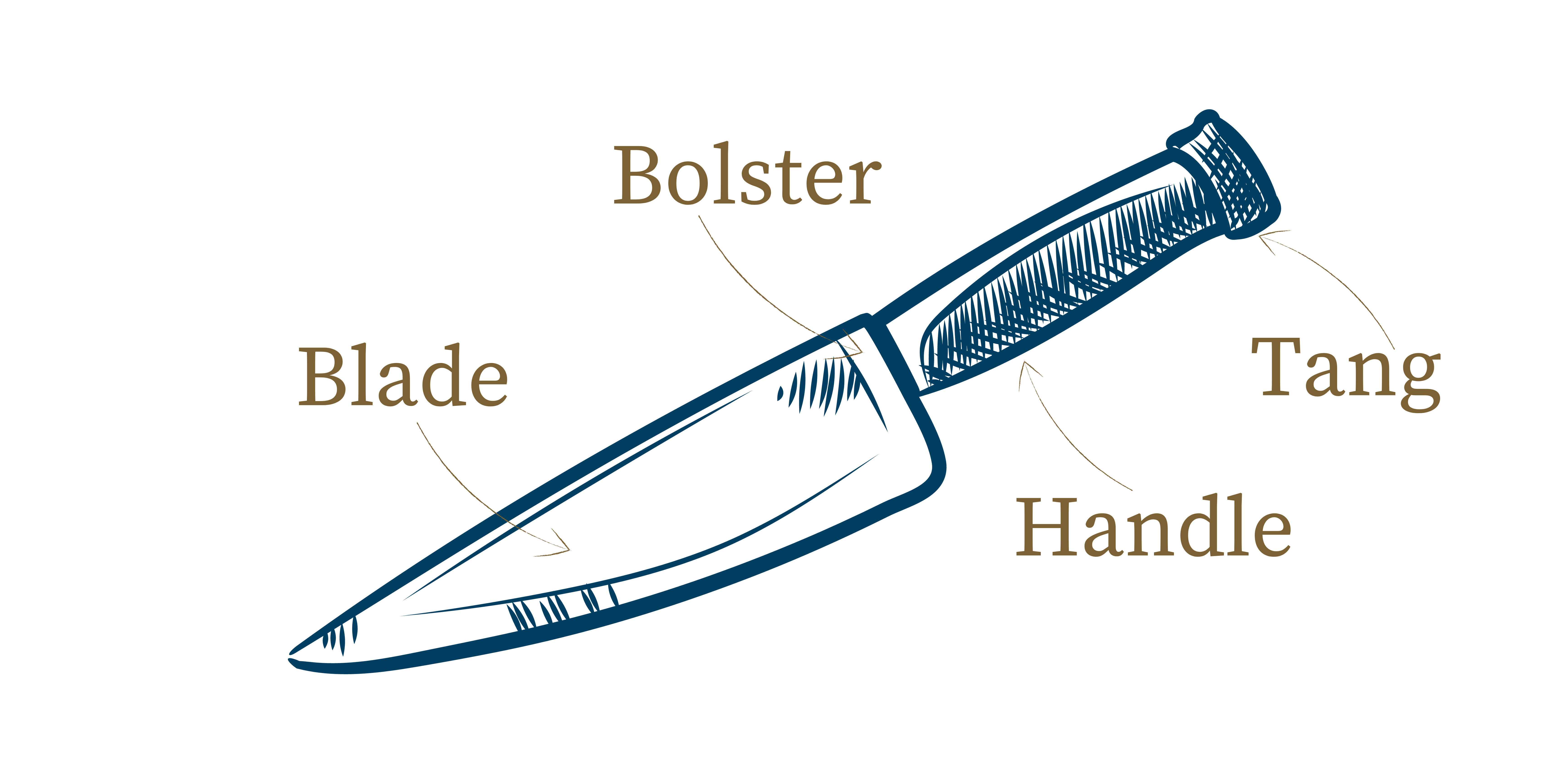

A bar of iron and a bar of steel would be forged together. In the first heat, the iron near the joint would be shaped into a bolster. The forger placed the iron between two dies called ‘prints’ which were held in tongs and the striker would hit the top die with a 14lb hammer. The short section of iron bar was then drawn out as a tang.

The steel bar, once cropped on the aggon (an inverted chisel set into a forger’s anvil), was called a ‘mood’. This was heated and drawn out to form the blade.

The forger led the work, determining the shape of the blade, while the ‘striker’ drew out the metal. Elements of the process would not be done sequentially on a single blade at a time, rather the forger would weld the metals, form the bolsters and draw out the tangs of a dozen or so knives before reheating them and drawing out the blade, to work most efficiently.

Today, most blades are stamped out of sheet steel using large presses.

The final step in the process for the forger would be to strike the manufacturer’s mark onto the blade. This was done on the ‘mark’ side of the blade near the bolster.

The blade would then be hardened and tempered, which allowed a cutting edge to be retained. Originally this would have been done by the forger, but by the later 19th century, a specialist hardener would have caried this out.

The steel blade would be heated to approximately 1000°C – gauged purely by the colour of the steel. It was then quenched in whale oil, brine or oil and water which hardens the steel in varying degrees, but made it brittle. Care was essential during quenching otherwise the blade would ‘skeller’ or twist.

Most of the oil would be wiped off before the blade was returned to the heat. The degree of hardness could be controlled by reheating to the desired temperature within a range of 150°C and 650°C. An increase in hardness would result a decrease in toughness. As such the tempering temperature could balance the degree of hardness and toughness.

Sources include:

- Unwin, J. The Development of the Cutlery and Tableware Industry in Sheffield (2002). In J. Symonds (Eds.), ARCUS Studies in Historical Archaeology 1 - The Historical Archaeology of the Sheffield Cutlery and Tableware Industry 1750-1900 (pp. 13-52).

- Unwin, J & Hawley, K. (2005) Sheffield Industries. Cutlery, Silver and Edge Tools. Tempus

- Wray, N. (2000). ‘One Great Workshop’. The Buildings of the Sheffield Metal Trades. English Heritage.