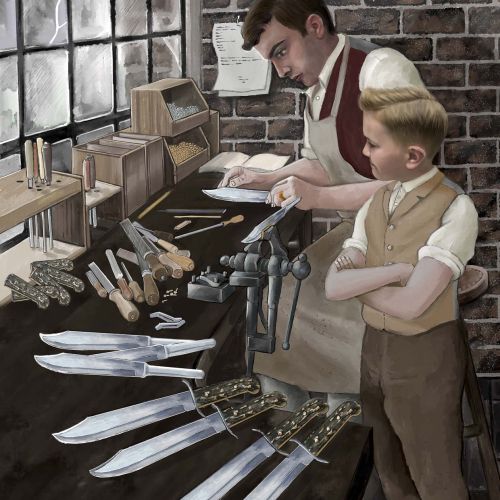

Heritage artwork at the Globe Works: Little Mester

Discover the story behind the artwork

Created by Wessex Archaeology in 2022, these panels were commissioned by the Globe Works to commemorate the outstanding and unique heritage of the building and depict people and scenes from its industrial past.

A Little Mester was someone that ‘owned their own work’, and were often cutlers. Cutling was a specialised job of assembling and hafting knives; fitting the handle to the blade and finishing the article ready for sale.

For lower quality knives, the end of long bones of cattle were cut to the general size and shape for table knife handles and hardwood was turned or cut into slabs forming scales and pinned on each side of the tang. For a middle quality knife, animal horn would be used, with the tips of antlers as well as the crowns being used for carving knives and forks. The best-quality table knives would have handles of ivory or more exotic woods, with pearl often used for fruit and dessert knives. Other materials were also used through the years, and by the second half of the 19th century plastics were also introduced including celluloid and xylonite.

There was a vast trade in the importation of exotic woods, ivory and pearl, and buffalo horn which resulted in a series of subsidiary trades Sheffield supplying handles and handle materials.

Cutlers required few tools, but included vices, small anvils, saws, boring tools, hammers and files. Small wooden trays called ‘workboards’ held the parts of the knives which were being assembled. The cutler would work at a work bench positioned beneath a window to make the most of the natural light.

The handle was attached to the tang, which could come in a variety of shapes. This shape would often influence the type and method of handle attachment. There are two basic types of tang – round and flat. Round tangs are by far the most common for table cutlery.

Handles were delivered to the cutler without the central hole for the tang, which the cutler would have to drill with precision. One method of ensuring the handle stayed on the knife with round tangs was to rivet over the tang as it passed through the handle, which required great skill, or resin would be used

Knives with flat, or ‘scale’ tangs are stronger in construction and use and are typically found in food preparation knives, and also required cheaper handles. The handle material was cut into two matching halves and attached to each side of the scale with two or three rivets. Bone and wood were the most common material used for this type of knife.

Another aspect of hafting was that of balancing the knife. The higher quality knives were balanced by means of a small lead weight inserted in the hole for the tang. This ensured that when the knife was placed on the table, the tip of the blade would not rest on the cloth.

Handles might be enhanced with the addition of a ferrule and endcap before the handle was pushed onto the tang.

The spring-knife cutler was considered the most skilled as the assembly process was the most complicated. It required the correct aligning of the spring, or back of the knife, and the blades to ensure their smooth opening and closing, along with the attachment of the inner and outer scales.

Once completed the knives would be returned to the grinders or buffers to be sharpened, buffed, glazed and cleaned prior to packing.

The following is taken from the 1843 The Penny Magazine which describes the cutler as working at:

“A small bench near a window, and is provided with a number of tools to facilitate his operations - such as a vice, a small anvil, several files, steel burnishers, a drill-bow and drills for boring holes, a glazer coated with emery, a polisher coated with oil and rotten-stone, steel plates to act as gauges in making holes through the various parts of the knife, and numerous other appliances which we cannot enumerate. With the aid of these he shapes and adjusts his various pieces, fastens them with pins or rivets, files down these pins to give them a neat and level appearance, polishers every part after it is fixed; and, in short, he does to a pen knife what every watchmaker does to a watch- he makes very few of the parts, but he adjusts them all.”

Sources include:

- Unwin, J. The Development of the Cutlery and Tableware Industry in Sheffield (2002). In J. Symonds (Eds.), ARCUS Studies in Historical Archaeology 1 - The Historical Archaeology of the Sheffield Cutlery and Tableware Industry 1750-1900 (pp. 13-52).

- Unwin, J & Hawley, K. (2005) Sheffield Industries. Cutlery, Silver and Edge Tools. Tempus

- Wray, N. (2000). ‘One Great Workshop’. The Buildings of the Sheffield Metal Trades. English Heritage.